International guidelines provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations on how to manage patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Guidance includes the appropriateness and optimal timing for percutaneous interventions as well as the ideal length of hospital stay.1–5 However, the current global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has posed an unprecedented challenge to acute and intensive care units (ICU), and forced many previously accepted clinical guidelines to be revisited and adapted across all medical and surgical specialties.6

In these circumstances, cardiology services and clinical pathways equally had to be rapidly modified and implemented.6,7 In this focused review, we discuss how COVID-19 has affected acute cardiology services, with particular focus on ACS. We propose pragmatic deviations from guidelines based on our local experience, as well as on those shared by other countries.8–10 Finally, we suggest strategies for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff when dealing with ACS patients. Whenever possible, we aim to provide support to proposed changes based on peer-reviewed literature.

Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Acute Cardiology Care

Global pandemics, such as COVID-19, can affect cardiology services at many levels, with some effects being particularly relevant to the care of ACS patients.

Firstly, there has been a need for a drastic adaptation of inpatient care and redistribution of beds, with many wards transformed into dedicated COVID-19 units. This shift has impacted inpatient cardiology capacity, led to cancellation and delays of elective work and affected the normally acceptable length of hospital stay for acute cardiology patients. Secondly, as ICUs have become largely dedicated to severely ill COVID-19 patients, there remains limited capacity for the recovery of cardiothoracic surgery patients or acute cardiology patients (e.g. cardiogenic shock following MI).

Another challenge is that patients with COVID-19 can present with ECG changes and a clinical syndrome of myopericarditis that mimics ACS, potentially increasing the number of false-positive ACS calls.11–13 Troponin elevation is observed in 18–23% of hospitalised COVID-19 patients, even in the absence of chest pain, with fulminant myocarditis being reported as directly responsible for up to 7% of COVID-19-related deaths.14–16 As per data available on 9 April 2020, close to 20,000 COVID-19 patients were hospitalised in the UK, which would create approximately 4,000 new ‘false diagnoses’ of ACS.17 Thus, while the incidence of true ACS cases has fallen since the beginning of the pandemic – possibly due to patients’ reluctance to attend hospital – cases of late-presenting MI and its complications have been described.18–20

Finally, healthcare workers working in cardiology face a higher than average risk of contamination, particularly those involved in potential aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs).21 This risk is especially high during ambulance transportation and echocardiography (because of close patient interaction) and urgent percutaneous interventions.7,22,23,24

Proposed Adaptations of Acute Coronary Syndrome Pathways

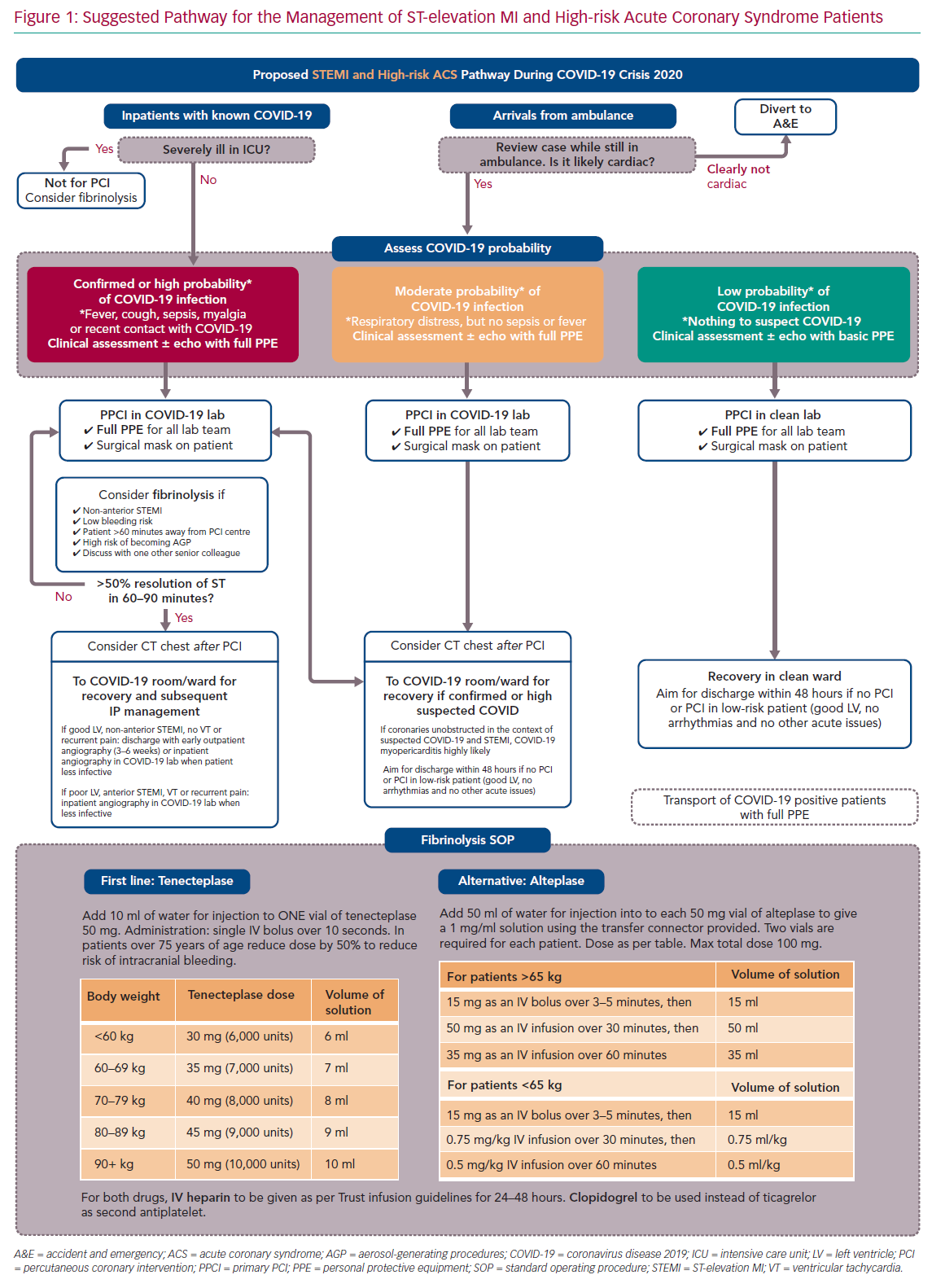

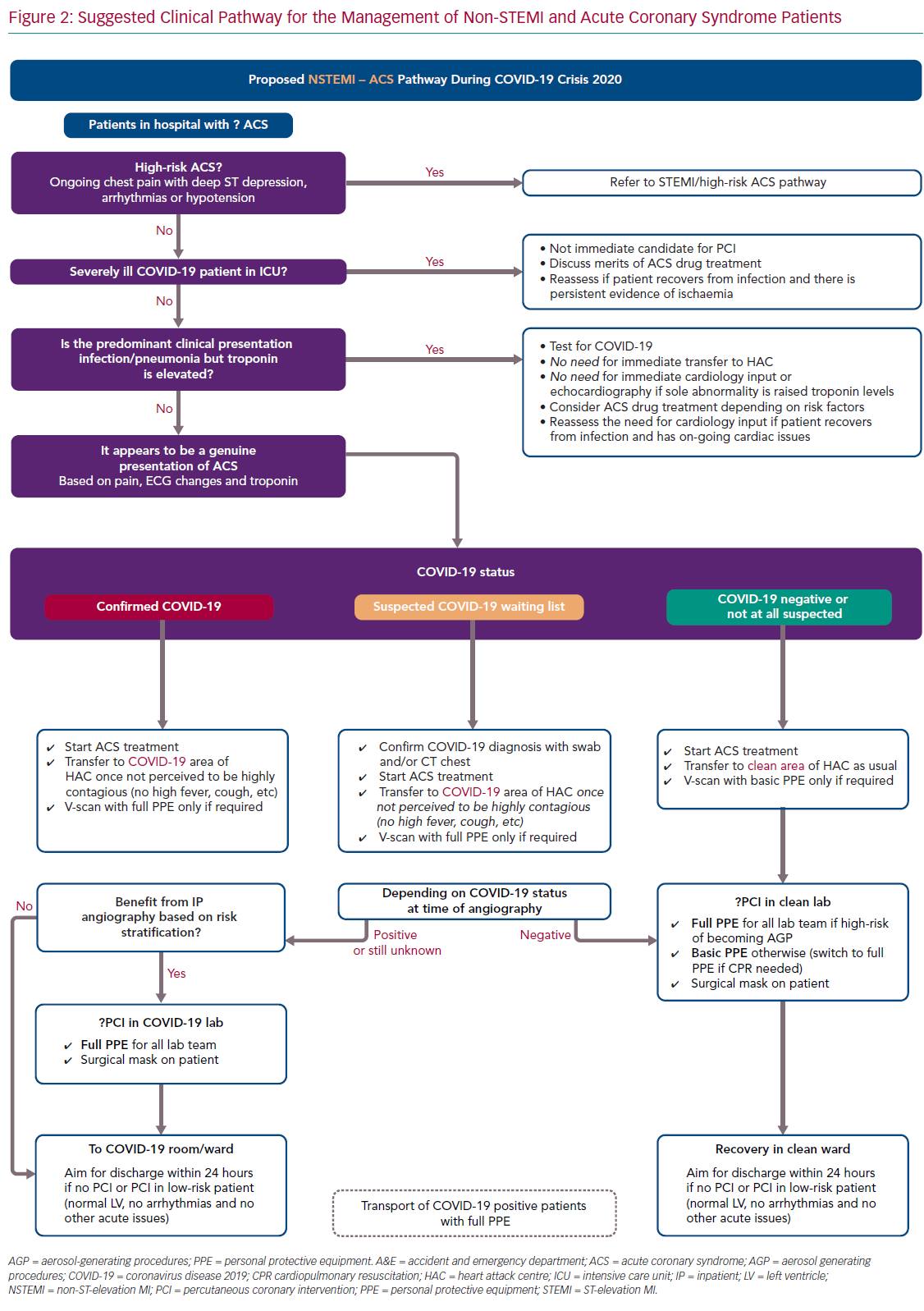

For ease of display we present the ACS pathways being used at our centre (Imperial College NHS Healthcare Trust, London, UK) as schematic flowcharts. Figure 1 displays the adapted pathway for the treatment of patients presenting with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and high-risk ACS and Figure 2 shows the modified pathway for non-STEMI (NSTEMI) and ACS.

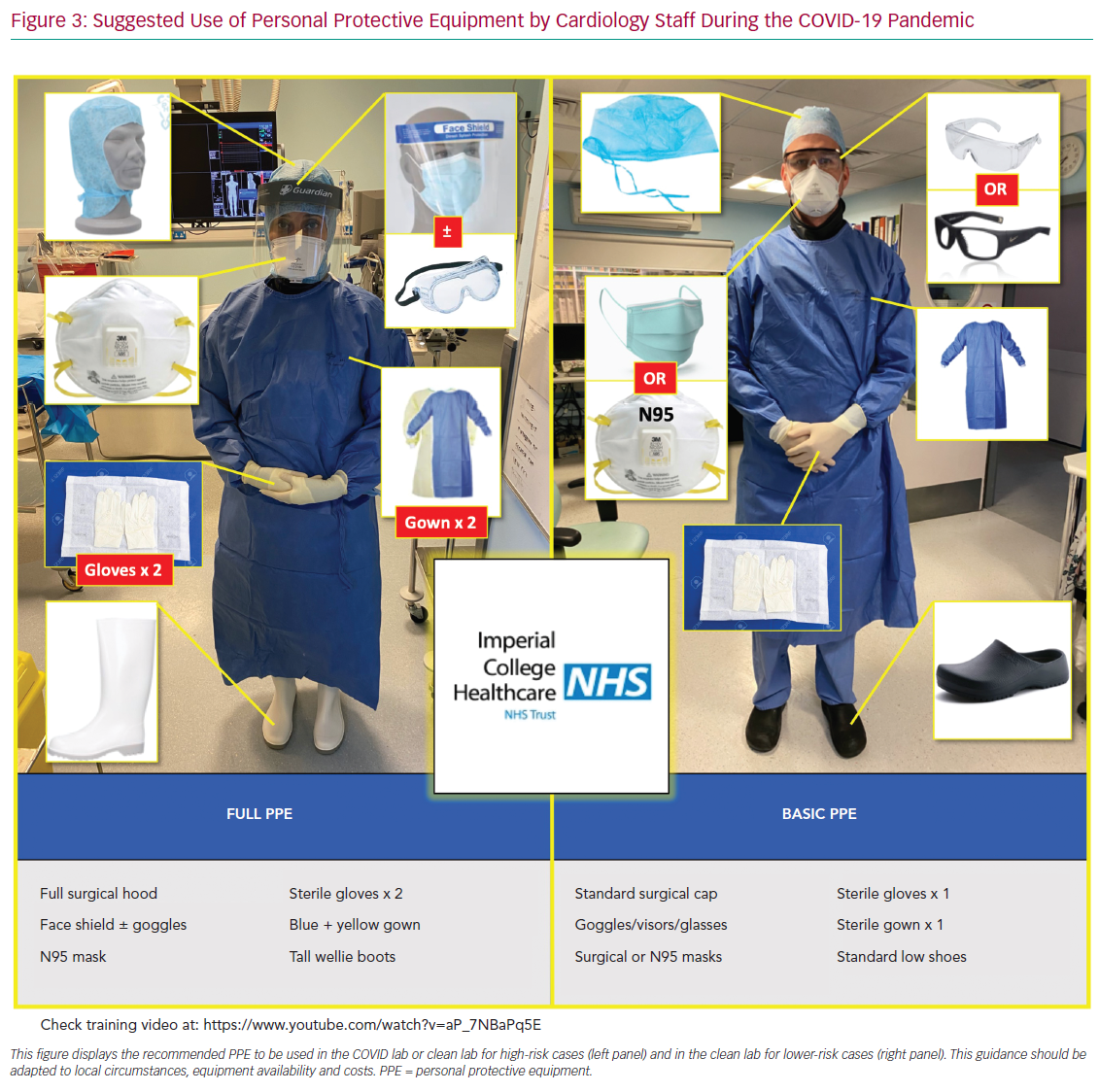

We briefly discuss the reasoning behind the most important deviations from guidelines, providing peer-reviewed evidence whenever possible. Our ACS pathways have been subjected to regional debates at the pan-London Heart Attack Centre Group and open public discussions at the Imperial College COVID-19 webinar, as well as on social media platforms and societal web content.25–27 Figure 3 summarises and displays our suggested protocol for the use of PPE by the cardiology team and catheter laboratory staff.

STEMI and High-risk Acute Coronary Syndrome

Our modified pathway to treat patients presenting with a STEMI or high-risk ACS is presented in Figure 1. The most relevant points for discussion are described in the following sections.

Reperfusion Strategies in Critically Ill Patients

Due to their high mortality and risk of transportation (for patients and staff), severely ill COVID-19 patients in ICU (patients requiring invasive organ support) who develop a STEMI or high-risk ACS should not be considered immediate candidates for emergency percutaneous revascularisation. Fibrinolysis could be considered on an individual basis following discussion with a senior colleague. If feasible, a rapid electronic multidisciplinary team meeting should occur between the clinicians involved, including intensivist, interventional cardiologist and general cardiologist, so that therapy can be administered in a timely fashion.

Triage of Patients Arriving From Ambulance Services

Up to the point of this paper being drafted, there is no approved point-of-care test for COVID-19 infection. Therefore, we suggest that patients presenting via ambulance with suspected STEMI should be assessed outside the arriving centre. In the UK, Heart Attack Centres such as our own are often based in separate units without general emergency care and so triage accordingly. If the case is clearly not cardiac based upon clinical grounds and ECG, patients should be diverted to the appropriate emergency department. This will avoid unnecessary viral exposure of hospital staff and ambulance crew caused by taking patients out of the ambulance. In centres with both emergency medicine and STEMI care, the decision is made between departments rather than between centres.

Identification of True STEMI Versus Myocarditis

COVID-19 can present as a STEMI-mimic myocarditis picture.13 Although this will result in emergency angiograms showing non-occluded coronaries, we judge that the only way of accurately reaching this diagnosis is via exclusion of STEMI. Therefore, the consideration of myocarditis as a differential diagnosis should not delay efforts to offer percutaneous reperfusion in possible COVID-19 patients presenting with chest pain and regional ST elevation on ECG. Radial angiography is recommended to reduce the risk of femoral bleeding complications.

Consideration of Lysis for COVID-19 Patients

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) should remain the preferred choice of revascularisation for STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, confirmed or highly suspicious COVID-19 patients (red box category on Figure 1) should be considered for fibrinolysis with staged PCI, particularly if the following clinical and/or logistical circumstances are present: the patient is not in a cardiac centre and transportation is likely to increase door-to-balloon time by more than 60–90 minutes; STEMI is not anterior and not involving a large myocardial territory on ECG; bleeding risk is low; patient is hypoxic and a potential high risk for generating aerosols during high-flow oxygen therapies, intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and there are no contraindications for thrombolysis.

The rationale for considering lysis therapy in such circumstances is the following: the survival benefit of PPCI over lysis is important but small – in the region of 2% absolute risk reduction in non-COVID-19 patients.28,29 Therefore it is likely that such benefit may be smaller or even abolished when an underlying pathology of high mortality, such as COVID-19 is present leading to inevitable delays in PCI reperfusion, caused by the inevitable delays in patient transportation and the extra time needed for protecting catheter laboratory staff members.30

In addition, transportation (from a general hospital to a cardiac centre) of highly infective COVID-19 patients, particularly those requiring high flow oxygen therapy, imposes a very high risk of contamination to healthcare workers, including ambulance crew and catheter laboratory staff.31–33

Finally, it is possible that offering PCI after COVID-19 infection has settled (fever, hypoxia, inflammation, etc) would reduce the risk of stent thrombosis. However, we believe it is important that pathways that include fibrinolysis are put in place in advance.

Firstly, decisions must be individualised and made by more than one senior physician, with the reasoning for offering lysis over PPCI being clearly documented in the patients’ medical records. Secondly, there should be a clear upfront revascularisation plan as to what to do if lysis is effective and – more importantly – if it is not and rescue PCI is needed. Finally, fibrinolysis protocols (agents, doses, contraindications, etc) should be reviewed and staff should be retrained, particularly if the centre does not use such reperfusion strategy routinely. In our pathway we present two possible drugs for lysis therapy (bottom of Figure 1).

Routine Use of CT before Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

While this has been suggested in some algorithms, our internal pathway does not involve routine use of chest CT to confirm the diagnosis of COVID-19 before PPCI. At a pre-PPCI stage, CT would not change immediate management for patients or staff (who will be offered full PPE in all STEMI cases, as per below PPE section) and it would delay reperfusion time significantly.34 We believe that CT should be considered after PPCI for further stratification and inpatient management if clinicians believe it would support diagnosis of COVID-19 or would alter management.35

Early Discharge of Low-risk Patients

Following STEMI revascularisation of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, early discharge will likely reduce the risk of contamination between patients and to healthcare workers.36 Therefore, low-risk patients (those with normal left ventricular [LV] function, no haemodynamic compromise and no evidence of malignant arrhythmias) should be offered discharge within 48 hours of presentation. Such an early discharge approach has already been documented to be safe in non-COVID-19 cohorts.2,37 More formal risk scores such as the Zwolle risk score could be used to help decision-making.38–39

Personal Protective Equipment for Staff and Subsequent Management

For STEMI and high-risk ACS patients, we propose to offer the catheter laboratory staff full PPE in all cases, regardless of their COVID-19 status (see Figure 3 and PPE section below). Protection with full PPE should also apply to any close clinical and echocardiographic assessment prior to transfer to the catheter laboratory. Subsequent inpatient management and ward allocation will still be determined by their COVID-19 status or probability of disease; those patients with confirmed or highly suspected COVID-19 should be transferred to appropriate COVID-19 wards.

On-call Rota Adaptations and Multidisciplinary Team Discussions

During the pandemic, it is reasonable to adopt a buddy system for rotas, with one consultant on-call and a second on stand-by in case the first one falls ill. In addition, social distancing measures have affected routine implementation of face-to-face discussions among physicians. Therefore, adoption of virtual multidisciplinary teams and data compliant group messaging allows for rapid decision-making deliberations during the pandemic. All discussions should be clearly documented in patients’ medical records.

Non-STEMI and Acute Coronary Syndrome

The NSTEMI–ACS pathway is presented in Figure 2. The points in the following sections should be highlighted.

Identification of False-positive Acute Coronary Syndrome Cases

COVID-19 infection in hospitalised patients is associated with elevation in cardiac troponin in a significant proportion of cases – up to 23% of cases in a Chinese cohort.15 The precise pathophysiological mechanisms behind this myocardial injury has not yet been established, hence optimal management remains unknown. Therefore, the management of raised troponin in COVID-19 patients should be individualised and guided by their clinical presentation: if the syndrome is infective and typical of COVID-19, there is no need for specific cardiology input, targeted ACS treatment or invasive angiography. Equally, although assessment of LV function in these patients might be of prognostic value in high-risk patients, routine inpatient echocardiography studies for all cases should be avoided as it would increase the risk of transmission to staff without affecting clinical management.40 There are ongoing studies assessing the role of antiplatelets and anticoagulation on COVID-19.41,42

Management of True Acute Coronary Syndrome Cases

If the clinical picture is typical of ACS, management should remain as standard as possible for stable patients, regardless of COVID-19 status.1–5 This includes prompt initiation of pharmacological therapy and transfer to a cardiac unit with catheter laboratory facilities.

We propose that patients should be offered invasive angiography before discharge, particularly those with raised cardiac biomarkers, high-risk ECG features or regional ventricular abnormalities on echocardiography. While an early conservative discharge on medical therapy alone would reduce hospital stay, the risk of reinfarction is considerable.43

Furthermore, because a significant proportion of patients will be unwilling to seek hospital attention again because of fears of acquiring COVID-19, we judge that early medical discharge would pose an unacceptably high mortality risk during the pandemic.44–47 Finally, most cardiology units have reduced elective work, therefore there should be capacity for early angiography to all suitable patients. The timing for invasive angiography should be guided by the patient’s COVID-19 status and infectiveness. Those with acute viral symptoms, high fever, cough and sepsis are most likely highly contagious. Therefore delaying angiography until such markers are settled should be safer for staff and should also in theory reduce the risk of immediate procedural complications, such as stent thrombosis.48

In confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients, we believe bedside echocardiography should be offered judiciously for those patients with a clear clinical indication, such as clinical heart failure or suspected valvular disease.22 Also, to minimise exposure for the operator, we agree with current society guidelines that echocardiographic studies should be focused and covered by full PPE.22,31 Finally, it is expected that short turnaround point-of-care COVID-19 testing will be available soon to help decision making. The timing of testing is important and we aimed for testing at the time of first clinical contact but no later than exit from the catheter laboratory.

Early Discharge

Following invasive angiography, the aim should be for an early discharge of all uncomplicated ACS patients, ideally within 24 hours of the procedure. This strategy has been previously demonstrated to be safe and would decrease the risk of infection transmission in hospital.37,49

Personal Protective Equipment and Strategies for Staff

WHO and Public Health England have issued guidelines on the use of PPE for healthcare workers.50–51 Hospitals and cardiology units have had to adapt them to their local acute and catheter laboratory circumstances, taking into account equipment availability and costs.52

In our view, it is prudent to assume that all ACS cases have a high probability of becoming AGPs (possibly requiring high flow oxygen therapy, airway intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation), posing a high risk of exposure to staff. Also, emerging evidence supports the idea that many other benign physiological phenomena such as coughing and talking loudly can potentially generate droplets and aerosols.53 Finally, experience from other centres and in our own have taught us that a significant proportion of acute patients coming in via ambulance who are not known to have COVID-19, develop symptoms while in hospital and a diagnosis of the infection will be made at a later stage.54

Therefore, we judge that during the peak of the pandemic, and if financially and logistically viable, the following PPE strategies should be adopted for ACS cases regardless of the patient’s COVID-19 status (Figure 3):

- Patients should wear a surgical mask during the entire hospital stay, providing it will not affect clinical care.55 Patients who require oxygen should have controlled doses administered via nasal cannula under the mask. Those requiring higher flows should be considered as an AGP.

- Close (<2 m) contact with patients should be restricted to the minimum necessary during ward rounds.

- It is reasonable to offer full PPE to all ambulance crew, catheter laboratory staff and echocardiography operators, as well as to acute workers with close clinical contact with the patient (Figure 3, left panel).

- For all other healthcare workers involved with direct patient care, a minimum of basic PPE should be provided (Figure 3, right panel).

- Thought should be given to the ventilation of catheter laboratory and ward areas as a way of promoting aerosol elimination.21,31,49

If departments face an issue of availability of PPE, it would be reasonable to offer basic PPE (Figure 3) to all staff when treating patients with very low probability of COVID-19 infection (green box on Figures 1 and 2). Importantly, this should be switched to full PPE in the event of AGP during PCI or hospital stay. For instance, patients suffering cardiac arrest would require staff in basic PPE to don full PPE before coming to provide support.

Limitations

Where possible, we have used high quality peer-reviewed data to guide these recommendations. However, at the time of writing, there was an urgent need to respond to an unprecedented medical emergency, which did not allow time for much data of this kind to emerge. Accordingly, we were required to make use of the pool of data available through direct communication, social media and preprints. We have maintained these in our references to remain true to the challenges of that period.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced cardiology departments to review previously established guidelines, particularly those affecting the care of ACS patients. However, based on shared global experiences and growing peer-reviewed literature, it is possible to put in place ACS treatment pathways that offer evidence-based decisions to patients and staff. While pathway modifications could be implemented more rapidly in the future, only further COVID-19 studies will guide us as to whether further modifications are needed.