Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is now the accepted treatment option of choice for patients presenting with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who are deemed to be inoperable or of high surgical risk.1,2 Short- and intermediate-term outcomes have been promising3–5 and with increasing institutional and operator experience combined with technological advancements there has been interest in the applicability of TAVI in the management of intermediate-risk6,7 and even low-risk8 patients. However, as with surgical bioprosthetic valves, there have been concerns with regard to the risk of early valve failure and durability.9,10

One potential limitation is the occurrence of early post-TAVI thrombosis.11 Following surgical valve replacement, the occurrence of thrombosis is associated with increased mortality and morbidity12,13 and in contemporary imaging studies has been reported to occur in up to 5 % of patients.14 TAVI thrombosis is thought to be more common than this14,15 and has been postulated to be an important contributing factor toward early valve degeneration with the development of poorly-mobile thickened valve leaflets and even possibly pannus formation.16 In the setting of transcatheter heart valves (THV) the mechanisms, frequency and optimal management strategy of thrombosis is currently poorly understood and based upon a small number of case reports and retrospective studies.15,17–20 Whilst the incidence of obstructive THV thrombosis is <1 %,20 the overall incidence is likely to be much higher with advances in imaging technology identifying up to 40 % of patients21,22 (the majority of whom are asymptomatic) following TAVI with valve appearances strongly suggestive of thrombosis.

The role of anticoagulation in the treatment of patients presenting with obstructive symptomatic THV thrombosis is well defined. However, optimal post-TAVI antithrombotic regimens and the management and the rationale of intervention for patients with asymptomatic non-obstructive pathology are currently uncertain. The diagnosis of early TAVI thrombosis and the role of anticoagulation therapy for the management of these patients are discussed in this review.

Possible Causes of Early TAVI Thrombosis

Factors contributing to the occurrence of early TAVI thrombosis are likely to be multifactorial. Patients with chronic renal failure, not being treated with an oral anticoagulant agent and with low left ventricular ejection fraction appear to be at higher risk of thrombosis.14,21 Furthermore there may also be mechanical, valve-related features that may increase the likelihood for the development of early thrombosis, with possible causes including moderate–severe regional underexpansion (≤90˚) or an intra-annular valve position.23

Diagnosis

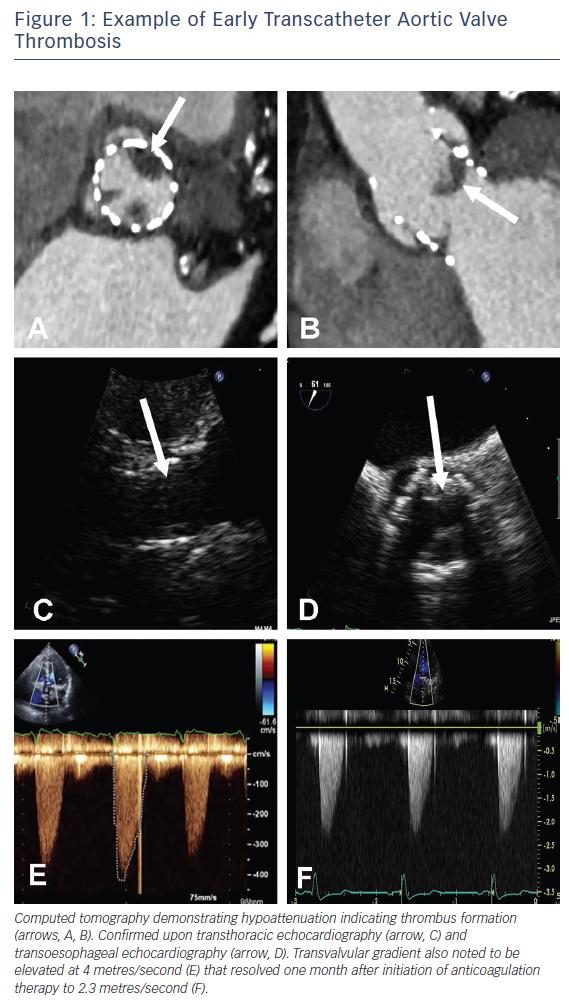

Prosthetic valve thrombosis is traditionally defined as any thrombus not caused by infection and that is attached to or near a surgical valve resulting in some degree of blood flow obstruction, interference with valve function, or is sufficiently large to warrant treatment24,25 and as such refers to symptomatic patients. Patients presenting with obstructive THV thrombosis commonly exhibit signs and symptoms of congestive cardiac failure. Historically, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has been the imaging modality most commonly used to evaluate prosthetic valve function and the presence of thrombus in this setting (Figure 1) and is invaluable in the assessment of transvalvular gradients, calculation of the effective orifice valve area and the presence of large thrombi.13 The confirmation of the presence of small thrombi is more challenging and in these instances, transoesophageal echocardiography – by virtue of its greater spatial resolution – may be useful in confirming a diagnosis. Most recently, technological advances in contrast-enhanced multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) have enabled it to become an invaluable adjunctive imaging modality with the presence of features including hypoattenuated leaflet thickening and ≥50 % reduction of leaflet motion26 further supporting the diagnosis of THV thrombosis (Figure 1).

A second group of patients who were previously poorly defined and are now increasingly being recognised, are those who present with abnormalities in valve appearance, leaflet movement or an increase in transvalvular gradients but without symptoms. Whilst no abnormality may be appreciable on TTE (with a ‘normal’ functioning valve), features supporting the diagnosis of THV thrombosis can be detected with the aid of MDCT.18,22,26 The natural history of this condition is currently unclear and CT sub-studies have been included as part of the recently launched randomised controlled trials investigating efficacy of TAVI versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low risk patients. The Placement Of Aortic Trascatheter Valves 3 (PARTNER 3) trial will include a 400-patient sub-study in an attempt to provide clarity on leaflet mobility and thrombosis among patients treated with the SAPIEN 3 (Edwards LifeSciences) and similarly the Medtronic low-risk study investigating the Evolut R device will also include a 400-patient CT substudy to further investigate this clinical entity.

Clinical Data

Data from a randomised trial and two registries have been analysed: the Portico Re-Sheathable Transcatheter Aortic Valve System US IDE (PORTICO IDE) trial, and the Assessment Of Transcatheter And Surgical Aortic Bioprosthetic Valve Thrombosis And Its Treatment With Anticoagulation (RESOLVE) and Subclinical Aortic Valve Bioprosthesis Thrombosis Assessed By 4D CT (SAVORY) registries.22 No patient receiving therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin (for other indications e.g. AF), compared with dual antiplatelet therapy, was noted to have reduced leaflet motion (trial: 0 % versus 50 %, p=0.01; pooled registries: 0 % versus 29 %, p=0.04) during follow-up.22 Furthermore, in patients found to have reduced leaflet motion, normal leaflet motion was restored in all 11 patients that subsequently received oral anticoagulation with warfarin, but in only 1 out of 10 patients not receiving anticoagulation (p<0.01).22 In a more recent study, the risk of THV thrombosis was 10.7 % in patients who did not receive warfarin versus 1.8 % in patients who received anticoagulation. Furthermore, subsequent treatment with warfarin resulted in normalisation of valve function in 85 % of patients.21 The efficacy of systemic anticoagulation with warfarin for the management of THV thrombosis is further supported by a number of case reports in the setting of both obstructive15,27,28 and non-obstructive29 valve thrombosis. Novel anticoagulants (NOAC) may also have a role in the management of these patients.19 Consequently, systemic anticoagulation is the cornerstone of treatment for patients presenting THV thrombosis early after TAVI.

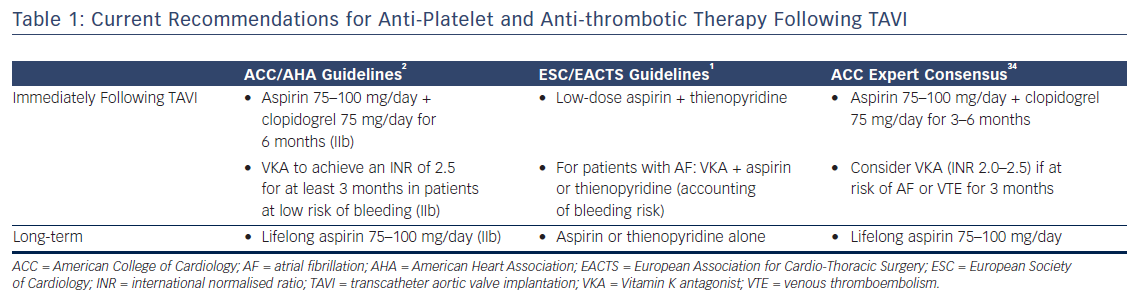

There is therefore considerable interest in understanding the optimal anti-platelet and anti-coagulant strategy following TAVI to reduce the risk of thrombosis. However, in view of the generally high-risk elderly population that are commonly treated with TAVI, the risk of bleeding has to be balanced against any theoretical benefit. Whilst predominantly designed for patients with coronary disease, current bleeding risk scores (e.g. Can Rapid Risk Stratification Of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation Of The ACC/AHA Guideline [CRUSADE]30 and Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network [ACTION]31) are often used in this population to determine bleeding risk prior to deciding upon a definitive strategy. The current guidelines for the administration of anti-platelet and antithrombotic agents following TAVI are summarised in Table 1.

Management

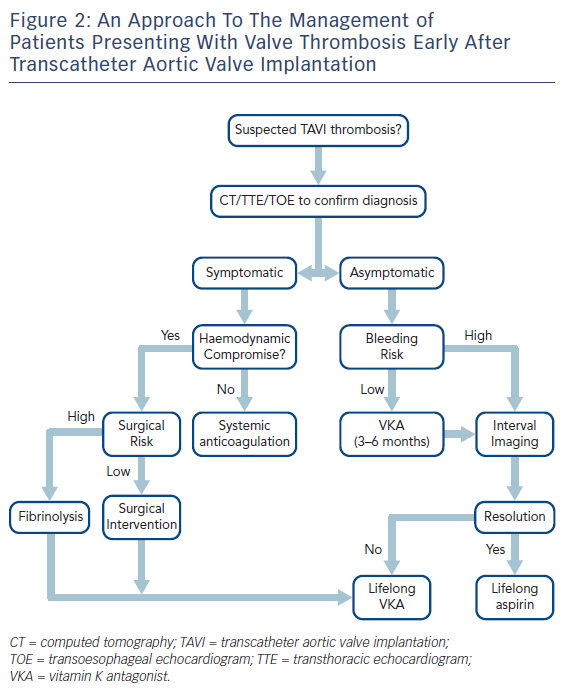

The management of patients presenting with early TAVI thrombosis varies between patients who are symptomatic and those who have subclinical thrombosis. This is further discussed in the subsequent sections and a flow chart illustrating a potential management approach is summarised in Figure 2.

Symptomatic THV Thrombosis

In patients presenting with obstructive (i.e. symptomatic) TAVI thrombosis, systemic anticoagulation should be initiated immediately with heparin. In patients in extremis (e.g. haemodynamic compromise), surgical intervention – including thrombectomy or valve replacement – should be considered.32 However, the majority of patients who have been treated with TAVI are likely to be deemed inoperable or of prohibitive risk for this approach because of concomitant comorbidities. In these instances, fibrinolysis should be considered32,33 followed by systemic anticoagulation with heparin and then warfarin.

In symptomatic patients who are haemodynamically stable, the anticoagulant agent of choice is currently warfarin. However, there have been reports of efficacy with direct oral anticoagulants.14,19 It is currently unclear as to the optimal length of treatment, with recurrence of THV thrombus noted following discontinuation of warfarin.22 Ideally, life-long therapy should be instigated but the final decision should be made on a patient-by-patient basis after balancing the benefits against the risks of bleeding in this high-risk patient cohort. If the decision is made to stop anticoagulation therapy, this should only be recommended when valve function has normalised and patients should be treated with long-term anti-platelet therapy with frequent clinical and echocardiographic surveillance with reports of recurrence with cessation of anticoagulant therapy.29

Asymptomatic THV Thrombosis

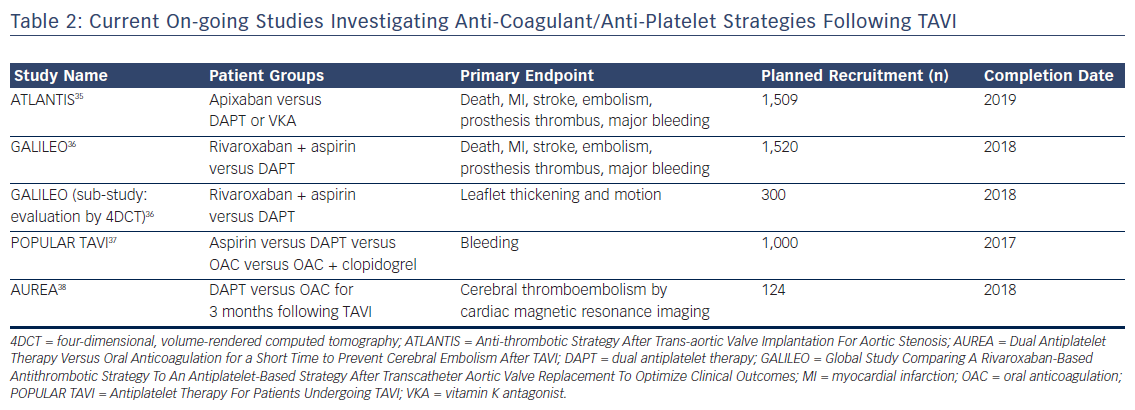

In patients presenting with asymptomatic or non-obstructive THV thrombosis (normal transvalvular gradients), the optimal management is uncertain. With advancements in MDCT, it is increasingly clear that this is a relatively common finding and, whilst it does appear to improve with systemic anticoagulation, there are reports of spontaneous resolution over time. Furthermore, and most importantly, the clinical sequelae are poorly characterised, with currently available data suggesting no difference in mortality or stroke but more transient ischaemic attacks in patients noted to have asymptomatic valve thickening.14 This is particularly important in view of the fact that initiation of anticoagulation therapy in this elderly co-morbid population is associated with a relatively high risk of bleeding complications. On the basis of the currently available data, routine anticoagulation following TAVI in this high-risk group cannot be currently recommended and is the subject of on-going study (Table 2).

Unresolved Issues

On the basis of current observations, there are a number of unanswered questions with regard to the management of patients presenting with THV thrombosis early after TAVI:

- The optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy for the treatment of THV thrombosis.

- Whether all patients should be ‘screened’ with MDCT for subclinical THV thrombosis and, if so, at what time-point.

- The benefit of routine post-TAVI anticoagulation to prevent the occurrence of valve thickening or reduced leaflet motion.

- The clinical relevance of non-obstructive asymptomatic valve thickening/reduced leaflet motion with regard to clinical outcomes and valve durability.

On the basis of the currently available data, routine systemic anticoagulation or screening MDCT to determine the presence/absence of valve thickening following TAVI is not recommended. However, a number of studies are on-going to investigate these issues further (Table 2), the results of which are eagerly awaited to determine optimal peri- and post-procedural anti-platelet and anticoagulant strategies.

Conclusion

Anticoagulation therapy forms the cornerstone of management for the treatment of early post-TAVI thrombosis. To date, warfarin has been the most commonly used agent and is associated with rapid improvement in the appearance and haemodynamics of TAVI valves in symptomatic patients. In patients presenting with obstructive symptomatic THV thrombosis, warfarin should ideally be continued for life. The clinical significance and the optimal management of patients presenting with asymptomatic non-obstructive valve thickening and/ or reduced valve motion is currently uncertain and is the subject of a number of on-going large-scale clinical trials.