Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and is the leading cause of death in women and men in Western societies.1 Despite the major advances seen in the field of interventional cardiology and pharmacotherapy, which have translated into better outcomes, a disparity is evident in the clinical outcomes between men and women.

This was clearly evident in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2018.2 The authors evaluated the outcome of 1,032,828 patients (258,713 women) included in 49 studies of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with respect to sex. Mortality was significantly lower in male patients at all follow-up time points – in-hospital mortality (OR 0.58; 95% CI [0.52–0.63];p<0.001); 30-day mortality (OR 0.64; 95% CI [0.61–0.66]; p=0.04); 1-year mortality (OR 0.67; 95% CI [0.60–0.75];p<0.001); and at least 2-year mortality (OR 0.71; 95% CI [0.63–0.79];p=0.005). The majority of studies included in the analysis had been published in the last 10 years, indicating that this issue remains relevant to contemporary practice.

The postulated causes for this disparity in PCI outcomes are multifactorial and include atypical presentation in women, delays in diagnosis and treatment in women, as well as the underuse of evidence-based medical therapies in female patients. The issue is compounded by the fact that women are under-represented in major trials, so extrapolating outcome data to the entire population may not necessarily be correct.

Acute Coronary Syndrome

There are pathophysiological differences in the causes of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with respect to sex. In men, there is typically rupture of a thin-capped atheromatous plaque which triggers thrombosis. Women are more likely to develop thrombosis caused by endothelial erosion.3 However, there is no evidence to suggest that this difference in pathophysiology should affect the treatment offered to patients. This is different to ACS caused by spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) which is significantly more likely to occur in women who account for 90% of patients and may be best managed medically.4

Despite advancements in the management of ACS, various studies have shown a clear disparity in the clinical outcomes between men and women, with women having worse outcomes.5–10 Women are more likely to present with atypical symptoms, have delays in the administration of treatment and therefore have longer ischaemic times.11 There is also evidence to suggest that women with ACS are less likely to receive evidence-based treatments and less likely to undergo cardiac catheterisation and revascularisation.5–7,9,12–19

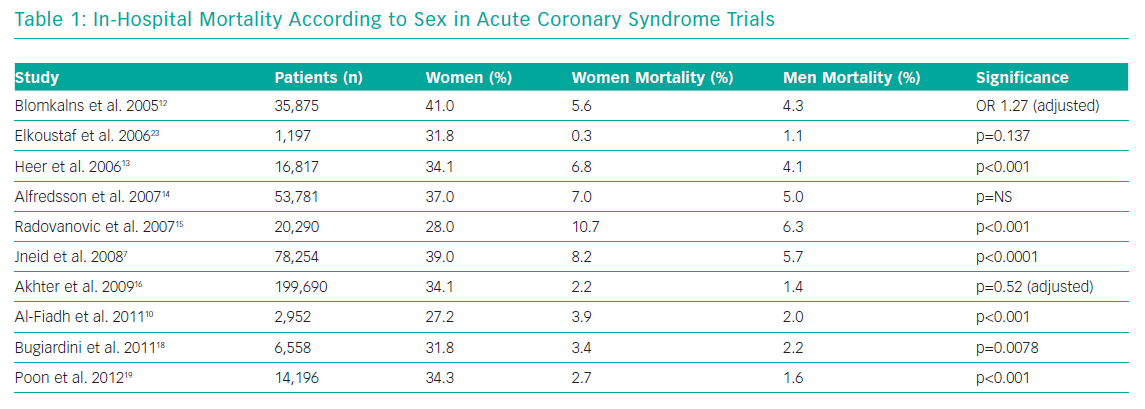

Table 1 demonstrates the in-hospital mortality according to sex in several ACS studies. The proportion of female patients in the studies ranged from 27–41%. The unadjusted mortality is significantly higher in women, although appears less so once adjusted for confounders.12,16

A large UK study evaluating the treatment of patients with ACS with respect to sex has been published this year.20 Women (n=238,489) comprised 34.5% of the study and were older (76.7 years versus 67.1 years) and less likely to present with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) (33.9% versus 42.5%). Women were less likely to receive guideline-indicated care when compared with men including timely reperfusion therapy for STEMI (76.8% versus 78.9%; p<0.001), and timely coronary angiography for non-STEMI (24.2% versus 36.7%; p<0.001).

Women also received sub-optimal medical therapy with less dual antiplatelet therapy (75.4% versus 78.7%) and less secondary prevention therapies (87.2% versus 89.6% for statins, 82.5% versus 85.6% for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blockers and 62.6% versus 67.6% for beta-blockers; all p<0.001). This study demonstrated that the 30-day adjusted mortality was higher for women than men – median 5.2% (interquartile ratio [IQR] 1.8%–13.1%) versus 2.3% (IQR 0.8%–7.1%; p<0.001) and the authors estimated that 8,243 deaths among women could have been prevented over the study period if they had been treated equally to the male patients.

Previous studies have demonstrated that when men and women receive similar treatment (including high use of an early invasive strategy in NSTEMI), there is no significant difference in 1-year mortality for women when compared with men, supporting the need for equality of care.21–23

Evidence supports the use of stent implantation for patients with coronary artery disease and ACS. However, a large French registry of 74,389 consecutive patients (30% women) demonstrated a lower rate of PCI with stenting in women having an acute MI (14.2% versus 24.4%; p<0.001).24 In the same study, the in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in women (14.8% versus 6.1%; p<0.0001). The Women in Innovation Initiative and Drug-Eluting Stents (WIN-DES) collaboration is an initiative set up to specifically evaluate outcomes of drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation in women. Recently published data demonstrates the safety and efficacy of the use of contemporary DES in 2,176 women after acute MI.25 At 3 years, the use of new-generation DES was associated with lower risk of death, MI or target lesion revascularisation (14.9% versus 18.4%; adjusted HR 0.78; 95% CI [0.61–0.99]) compared with first generation DES, as well as definite or probable stent thrombosis (1.4% versus 4.0%; adjusted HR 0.36; 95% CI [0.19–0.69]).

Invasive Strategy in Non-ST-elevation MI

The benefit of an early invasive strategy for non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) is less clear in women compared with men, with some studies suggesting they might even have worse outcomes. This has been attributed to older age at time of presentation, presence of multiple co-morbidities and smaller body habitus.26,27 Both the Fragmin and Fast Revascularisation during InStability in Coronary artery disease (FRISC) II and the three Randomised Intervention Trial of unstable Angina (RITA) trials demonstrated a clear benefit for a routine early invasive strategy in men; however women in the invasive strategy groups had worse outcomes.28,29

Further analysis of the FRISC II trial demonstrated that the higher event rate in women treated with an early invasive strategy seemed largely due to an increased rate of death and MI in the women who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) as the means of revascularisation. Conversely, the Treat Angina with Aggrastat and Determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction-18 (TACTICS-TIMI 18) trial did show benefit of an early invasive strategy in both sexes.30 In patients with elevated biomarkers, there was a reduction in the primary endpoint of death, MI or rehospitalisation for ACS at 6 months.

A subsequent meta-analysis did lend support to the use of an early invasive strategy in women in the presence of elevated biomarkers.31 Furthermore, the large Swedish Web-System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry of 46,455 patients also demonstrated that an early invasive strategy for NSTEMI was associated with a marked and similar reduction in mortality in women (RR 0.46; 95% CI [0.38–0.55]) and men (RR 0.45; 95% CI [0.40–0.52]).22 These data indicate that in women with elevated biomarkers, an early invasive strategy is warranted and women should therefore be undergoing angiography at a comparable rate to that of their male counterparts.

ST-elevation MI

The literature demonstrates that the benefit of early reperfusion therapy in STEMI in both sexes is unquestionable and this is reflected in current practice guidelines.32 Nevertheless, women presenting with STEMI are less likely than men to be admitted to a hospital which has the ability to perform PCI.33

The mortality rate of women after STEMI is higher than that of men. In one meta-analysis of 68,536 patients (27% female, n=18,555), mortality was higher in women both in hospital (RR 1.93; 95% CI [1.75–2.14]; p<0.001) and at 1 year (RR 1.58; 95% CI [1.36–1.84]; p<0.001).34 However, women tend to be older and have more co-morbidities with a higher rate of diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol. When these factors were taken into account, the higher 1-year mortality rate in women was no longer evident in this meta-analysis (RR 0.90; 95% CI [0.69–1.17]; p=0.42).

Contrary to this, a recent study analysed patient-level data from 10 randomised trials and evaluated the rate of death or heart failure hospitalisation within 1 year.35 The study evaluated 2,632 patients (22% female, n=587) and found that, despite there being no difference in the size of infarct, the adverse event rate was higher in women at 1 year: the mortality was 3.5% versus 1.8%, p=0.01; and death or heart failure hospitalisation rate was 7.9% versus 3.4%, p<0.001. When adjusted for age, risk factors and infarct size, the risk of death or heart failure hospitalisation was still significantly higher in women (adjusted HR 2.13; 95% CI [1.34–3.38]; p=0.001).

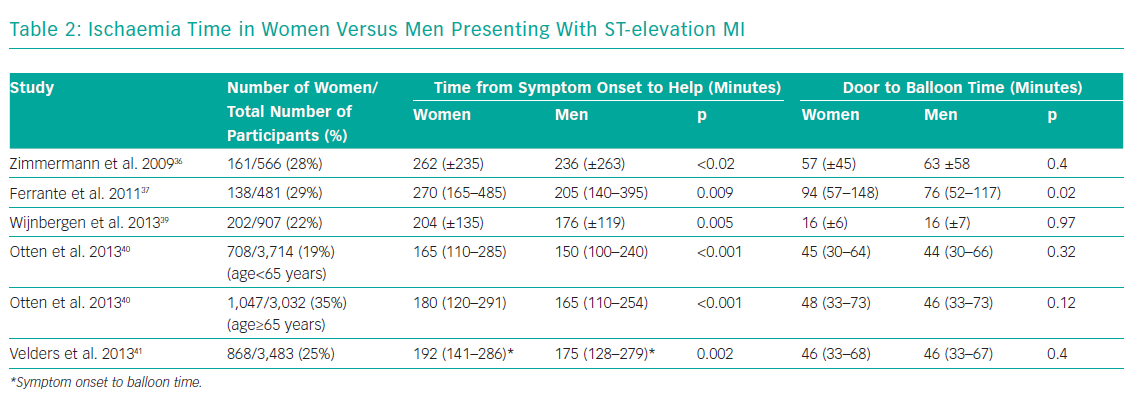

Several studies consistently demonstrate longer ischaemia times for women presenting with STEMI, driven mainly by a delay in seeking help (Table 2).36-41 A large national study from Poland of 26,035 patients (34.5% women), showed that significantly fewer women with STEMI underwent primary PCI within 12 hours from symptom onset (35.8% versus 44.0%; p<0.0001).38 Both the time between the onset of symptoms to balloon time – 255 minutes (IQR 175–375) versus 241 minutes (IQR 165–360), p<0.0001 – as well as the door to balloon time – 45 minutes (IQR 30–70) versus 44 minutes (IQR 30–68), p=0.032 – were longer.

The multicentre Examining Heart Attacks in Young Women (VIRGO) study evaluated 1,465 patients aged 18 to 55 years admitted with STEMI.42 This US study was specifically designed to evaluate outcomes in young patients admitted with STEMI with respect to sex and it enrolled more women than men. In accordance with other studies, women were more likely to have atypical symptoms and presented later. Of those patients deemed suitable for reperfusion therapy (women=761; men=477), the study found that women were more likely to be untreated (9% versus 4%; p=0.002) and women who did receive reperfusion experienced a longer delay to receiving therapy. 42

Mortality in STEMI is strongly associated with ischaemic time – every 30-minute delay of revascularisation increases annual mortality by 7.5%.43 One contributor to delay is that women do not perceive heart disease as a risk to their own health.44,45 The delay in women seeking help appears to be irrespective of age.40,42 It is therefore important that public health campaigns highlight the need for all women to seek medical help promptly. Awareness should be raised among medical professionals to ensure that therapeutic pathways are optimised for women, particularly in those with an atypical presentation.

There is some evidence to suggest that PCI for women presenting with STEMI may be more challenging. Patients who have an unsuccessful PCI procedure for STEMI that fails to restore perfusion have an increased mortality. In a registry of 2,900 consecutive STEMI patients, failed PCI occurred in 4% and was associated with a significantly increased risk of both in-hospital (18% versus 4%) and long-term death (48% versus 14%, p<0.05).46 In this study, female sex was an independent predictor of PCI failure (OR 1.54; 95% CI [1.01–2.38]) and the authors concluded that special care should be taken when PCI is performed in women who are at higher risk for failure when presenting with STEMI.

Stable Angina

Women are also less likely to receive optimal medical therapy for stable angina compared with men. One observational study evaluated 3,779 patients (42% female) from the Euro Heart Survey.47 Women were less likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography (49% versus 31%; p<0.001), and even in those with proven coronary artery disease (CAD), revascularisation was performed in significantly fewer women than men (adjusted OR 0.70; 95% CI [0.52–0.94]; p=0.019). Women were also less likely than men to receive aspirin (73% versus 81%; p<0.001) and statin therapy (45% versus 51%; p<0.001). Importantly, in patients with confirmed CAD, women were more likely to die (2.9% versus 1.5%) or have MI (5.8% versus 2.7%) during follow-up.

There is some evidence to suggest that women may have poorer outcomes after PCI, both in terms of adverse clinical events as well as target vessel failure.48–50 One of the possible contributing factors to this could be that women have smaller coronary vessels compared with men. PCI in small vessels is associated with a higher rate of restenosis and target vessel failure. The benefits of using DES rather than a bare metal stent are greater when treating smaller vessels. Contrary to this, the German Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte registry of patients stented between 2005 and 2009 (100,704 stent implantations) found that despite having smaller vessel size, women were significantly less likely to receive a DES compared with men – 28.2 versus 31.3%, adjusted OR 0.93; 95% CI [0.89–0.97].51

Numerous studies of DES have demonstrated efficacy irrespective of sex.52–54 The multicentre Clinical Evaluation of the XIENCE Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System in the Treatment of Women With de Novo Coronary Artery Lesions (XIENCE V SPIRIT Women) study specifically evaluated the outcomes of 1,573 women treated with everolimus-eluting stents.55 The adverse event rate (death, MI or target vessel revascularisation) was 12% at 1 year and 15% at 2 years. These data were compared with male patients enrolled into the SPIRIT V study and once again female patients had a longer delay to therapy. The total referral time for coronary intervention in women was 4 days longer than that for men (p=0.0003). This may be attributed to the fact that women were more likely to have atypical angina (9% versus 6%) or indeed no chest pain (17% versus 13%) compared with men.

Complex Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

The WIN-DES collaboration has published data demonstrating the safety and efficacy of the use of contemporary DES in 4,629 women treated for complex CAD (defined as total stent length >30 mm, two or more stents implanted, two or more lesions treated or bifurcation lesion).56 Compared with non-complex PCI, women who had complex PCI had a higher 3-year risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (adjusted HR 1.63; 95% CI [1.45 to 1.83]; p<0.0001). The use of new-generation DES for complex PCI, compared with first-generation stents, was associated with significantly lower 3-year risk of MACE (adjusted HR 0.81; 95% CI [0.68–0.96]), target lesion revascularisation (adjusted HR 0.74; 95% CI [0.57–0.95]), and definite or probable stent thrombosis (adjusted HR 0.50; 95% CI [0.30–0.83]).

Left Main Stem Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Disease of the left main stem (LMS) merits specific attention as revascularisation confers prognostic benefits over and above medical therapy alone. Although CABG is the gold standard, recent trials have supported the concept of PCI as a revascularisation modality for patients without a heavy burden of concomitant disease indicated by a low or intermediate SYNTAX score.57 The outcome of PCI for LMS disease is dependent on the complexity of disease. Lesions that involve the bifurcation are subject to a higher rate of adverse events, driven mainly by the need for repeat revascularisation.58 Women may be more likely than men to have disease at the ostium of the LMS.59 Studies have shown that PCI for ostial LMS disease has a low rate of MACE not significantly different to the results after CABG.60

As with other revascularisation trials, women have been relatively under-represented in the studies of LMS disease comparing PCI with CABG. However, a study by Buchanan et al. specifically evaluated the outcomes of 817 women after PCI versus CABG for unprotected LMS disease.61 Propensity matching was used to identify 175 pairs and demonstrated no difference in death, MI or stroke. There was an increased need for repeat revascularisation in the group treated with PCI compared with the CABG group. This risk of restenosis may be compounded in women because of their smaller vessel size; in one angiographic study, the mean LMS diameter was 3.9 ± 0.4 mm in women versus 4.5 ± 0.5 mm in men.62

The Evaluation of XIENCE Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery for Effectiveness of Left Main Revascularization (EXCEL) trial was a randomised study designed to specifically evaluate the outcomes of 1,905 patients with LMS disease randomised to either PCI with everolimus-eluting stents versus CABG.63 At 3 years, PCI was found to be non-inferior to CABG for the primary composite endpoint of death, stroke or MI. However, the study found that women undergoing PCI had worse outcomes (19.7% versus 14.1% for the primary composite endpoint) and might be better treated with CABG.

A recent analysis was undertaken to explore this further.64 Investigators showed that compared with men, women in the EXCEL trial were older, had a higher rate of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes and there were fewer smokers. However, they also had lower coronary anatomic burden and complexity of disease (mean SYNTAX score 24.2 versus 27.2; p<0.001). On multivariate analysis, sex was not an independent predictor of the primary endpoint at 3 years (HR 1.10; 95% CI [0.82–1.48]; p=0.53). However, women treated with PCI had a higher rate of peri-procedural MI compared with men and the authors concluded that sex is an important factor to be considered and that further studies are required to determine the optimal revascularisation modality for women with this type of complex coronary artery disease.

Peri-procedural Complications

A major concern has been that women undergoing PCI have been shown to have higher rates of peri-procedural bleeding and vascular complications compared with men.26,65–67 Registry data demonstrate that women are more likely to have vascular complications, contrast-induced nephropathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, stroke, infection and death. Women are more likely to suffer femoral complications requiring vascular intervention and retroperitoneal haemorrhage. Major bleeding and receiving a blood transfusion for any reason is strongly associated with MACE and mortality.68

The issue of vascular complications and bleeding has been mitigated by the switch to using radial access for PCI. Although women have an increased rate of radial access failure due to the relatively small size and problems of radial artery spasm, this route is still feasible in the vast majority.

The Study of Access Site for Enhancement of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (SAFE-PCI) involved 1,787 women undergoing either catheterisation or PCI randomised to either radial or femoral access.69 There was no significant difference in the primary efficacy endpoint, however there were significantly fewer bleeding and vascular complications in the radial group (0.6% versus 1.7%; OR 0.32; 95% CI [0.12–0.90]).

Additional large randomised studies have also supported the use of a radial approach in reducing vascular complications and bleeding.70,71 One of these, the MATRIX trial, enrolled 8,404 patients (26.7% women) and specifically evaluated the impact of sex.72 After adjustment, the overall adverse event rate was not significantly different for men versus women, however women still had an overall higher risk of access-site bleeding (RR 0.64; p=0.0016), severe bleeding (RR 0.17; p=0.0012) and need for transfusion (RR 0.56; p=0.0089). The benefit of trans-radial access in reducing MACE was more evident in women than in men and was statistically significantly (RR 0.73; 95% CI [0.56–0.95]; p=0.019) compared with the use of a femoral approach. Notably, although the radial approach was successful in the majority, the crossover rate for those randomised to a radial approach was higher in women than in men (7.6% versus 5.2%).

Conclusion

In contemporary PCI practice, there remains a disparity between the outcomes of women versus men, with women having significantly worse outcomes and a higher mortality. The causes are multifactorial and relate to differences in health-seeking behaviour as well as sub-optimal medical therapy. Women are less likely to undergo cardiac catheterisation and revascularisation; are not treated as quickly as men; and are less likely to receive optimal pharmacotherapy.

There is no data to suggest that women benefit any less than men from guideline-recommended primary and secondary prevention cardiovascular medication and revascularisation. Medical professionals need to ensure that the management of women is not biased by a perception of increased risk, such as bleeding, which might potentially deny women from receiving evidence-based therapies. Future studies should focus on evaluating health behaviours, patterns of disease and clinical outcomes, in a sex-specific way.